Words and photos by Nathalie Cantacuzino

One of my earliest memories of Christmas in Stockholm is spending it at our turn-of-the-century apartment on Karlavägen, located in central Stockholm. It was the early 90’s, and one of the rare moments when our family was gathered, yet undivided. My mom, being Russian and having a flair for dramatic extravagance, forced a not-so-amused myself and my elderly sister to wear dark green and purple velvet dresses with color-matching headbands, looking like a USSR version of Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander.

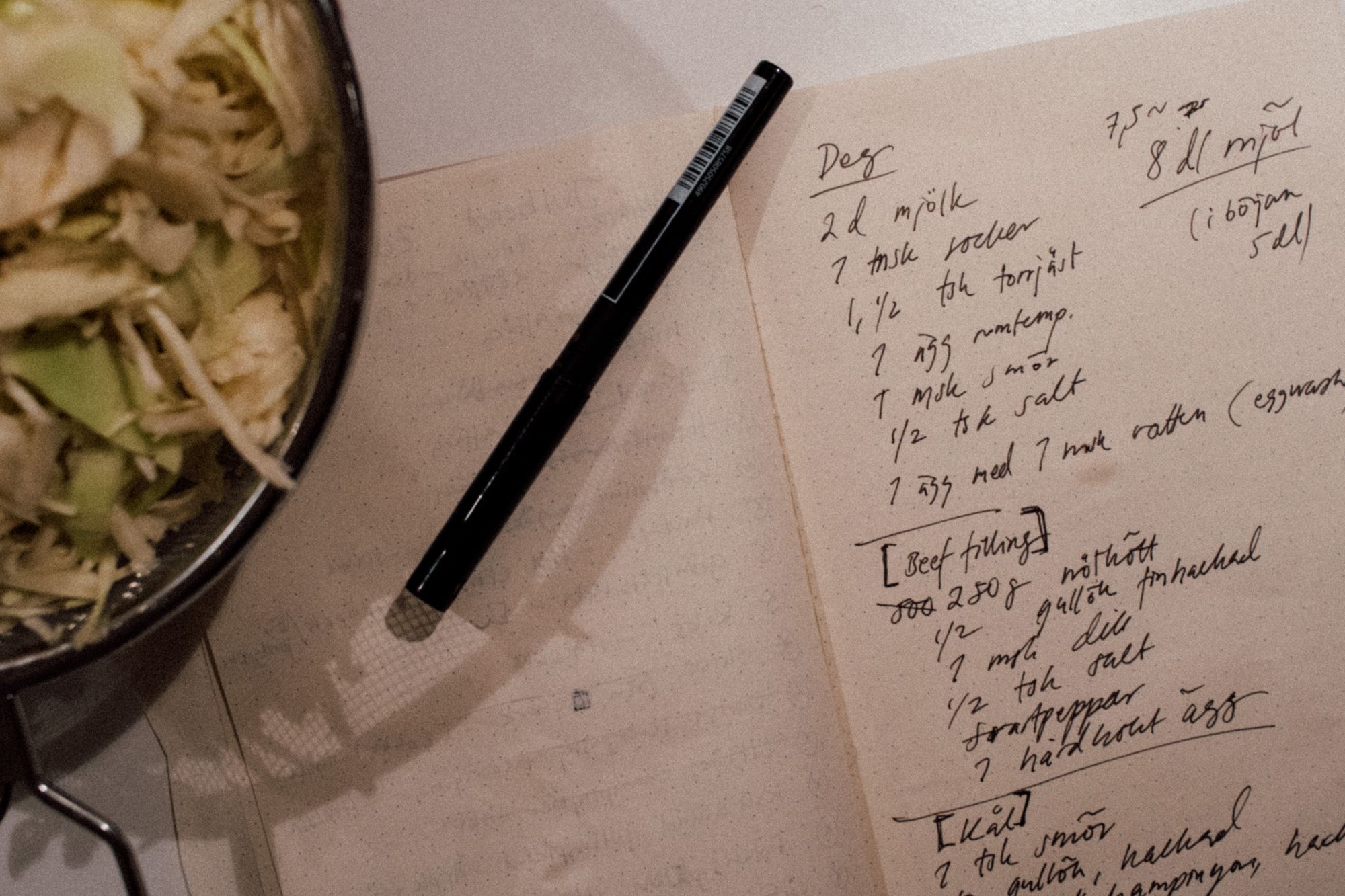

Coming from a first-generation immigrant family with roots in Russia and pre-communist Romania, our Christmas spread consisted of Swedish Christmas classics such as gravadlax, meatballs, and cocktail sausage, as well as home-made borscht and piroshki filled with cabbage and minced meat. It was a miraculous and rare occasion when my mom cooked, and though this annual display of her repertoire was still kept to a minimum, her piroshki – two days in the making – were filled buns of sheer happiness, challenging every eater not to go for seconds.

For those people unknown of the seasons of Scandinavia, Wintertime in Sweden is dark. When I say dark, I mean a void of soul-sucking dementors kind of darkness. Four bleak hours of daily sunlight accompanied by icy temperatures that sliver into the core of your being, squeeze out any chance of spontaneous outdoor activity. Finding pockets of light amidst the gloom becomes necessary for mental survival, and food is one of the ways Swedes cope with the four-month-long absence of the sun.

Taking a closer look at all the things that typically earn a spot on the Christmas table, what is essentially ‘Swedish’?

Swedish Julbord – literally, ‘Christmas table’ – is divided into three parts. The first plate is usually fish – often pickled herring or gravadlax. Second, come cold cuts – including smoked Christmas ham – along with prinskorv (cocktail sausages). Warm mains enter with the third course, dishes such as meatballs and a potato and anchovy casserole called Janssons frestelse. Sweet breads like saffron bread and kanellängd (cinnamon bread) are also a Christmas season staple, coming in an array of shapes and fillings; they’re eaten both alongside meals and any place fitting after a bakery visit.

These Swedish Christmas classics are enthusiastically devoured throughout all of Sweden as December makes its entrance – but just as intensely despised as the month comes to an end.

As I take a stab at a small pan-fried prinskorv with the swift flick of my fork, I don’t give much thought to the historical journey it has gone through, coming from 19th-century Austria to reach this point of time. Nor do I have any qualms about saffron bread not belonging on my list of mandatory Yuletide baking, although most Swedes probably don’t bake them in honor of Norse God Freja's favorite cat anymore. Instead, its distinctive flavor and bright yellow color act as an uplifting placebo, replacing the nordic sun that lies in temporary hiding – “Maybe if I eat enough bright-colored saffron buns, the darkness won’t swallow me.” Finally, no IKEA cafeteria in the world would dare to remove ’meatballs’ from their menu, despite their 18th-century Ottoman origin. It’s said that Swedish King Charles XII brought them back home after eating the local delicacy when visiting on state business.

These fragments of food history are recreated in the homes of millions of Swedish people every year. Although never the same and always in constant change due to new cultural influences and changing eating trends, we tell ourselves they are still quintessentially unchanged Swedish traditions.

Making the piroshki my mom used to make this year by myself, for the first time since my mom passed, feels almost ceremonial. While they didn’t come out precisely the same as hers, I thought much about the power that lies in continuation. Why do we keep making the same, slightly mediocre, dishes over and over again every year?

Traditions are continued because we as humans are overflowing with love for nostalgia and memories of food. Besides the comfort of familiarity that comes from repetition, there lies a longing for sharing one’s intimate food tradition with people, regardless of whether they are old friends or new. Whether it’s ordering an extra big-sized box of KFC and pre-made strawberry shortcake, as typical in Japan, or making sure there are five different types of pickled herring on the Christmas table, as in Sweden, the continuation of these traditions reflects us as modern humans perhaps more than anything else.

Unless a majority of the Swedish population suddenly wakes up on Christmas Eve with a serious craving for mince piroshki, I wouldn’t consider calling them authentic traditional Swedish Christmas food. But as a second-generation Swedish immigrant, they play a small but significant part of modern Sweden.

If you liked this article, please consider supporting APPETITE. Your donation will go towards project costs and paying creatives. One-off donations start from $5 via Buy Me a Coffee.