By Selena Hoy

Illustrations Misaka Hata

Paper strips with calligraphed kanji characters hang from the walls, chefs shout “irrashai!” as customers come through the door and servers place flasks of sake next to bowls of bright green edamame. Next door, a line curls around the corner as people step up to a ticket machine and feed coins in to choose their favorite bowl of ramen. Down the street, a family peers into a glass case; inside, perfectly rendered tempura shrimp stands next to glistening banana and strawberry parfaits, all formed from plastic. Restaurant-going in Japan can be a fascinating and bewildering experience.

Part of it is the myriad ways that menus are presented to the customer. Those paper strips, ticket machines, and beautiful plastic food displays are joined by digital touchpads, picture menus, and, of course, regular text menus. Bemused diners may not realise it, but when they take a ticket from a machine or salivate over plastic food displays, they're taking part in a tradition going back hundreds of years.

Feasts of fancy

The first incarnation of menus in Japan had little to do with restaurants – menus were records of meals for the elite, kept for posterity. These descriptions, rendered in calligraphy, were of the food served at banquets for visiting lords and dignitaries and the like, rather than a list of dining options to be chosen.

The 1671 book “Ryori Kondate-shu” (“Collection of Cooking Menus”) – the first printed compendium of menus in Japan – detailed such banquets, arranged by season. Japanese food and culture historian Eric Rath writes that some of these early menu books divided the menus into high, middle, and low ranks, with the highest-ranking menus – featuring luxury ingredients like crane, spiny lobster, and water chestnuts – reserved for shoguns, lords and other elites, while lesser menus were for middle and lower ranking samurai and commoners.

The first incarnation of menus in Japan had little to do with restaurants menus were records of meals for the elite, kept

for posterity.

Specialization and street stalls

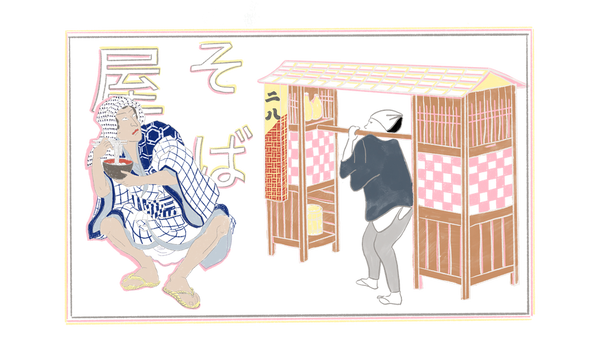

Before restaurants became common in Japan, some inns served food to lodgers, and teahouses served tea and light snacks to travelers. During the Edo period (1603-1868) yatai street stalls serving busy laborers prospered in the flourishing cities of the time.

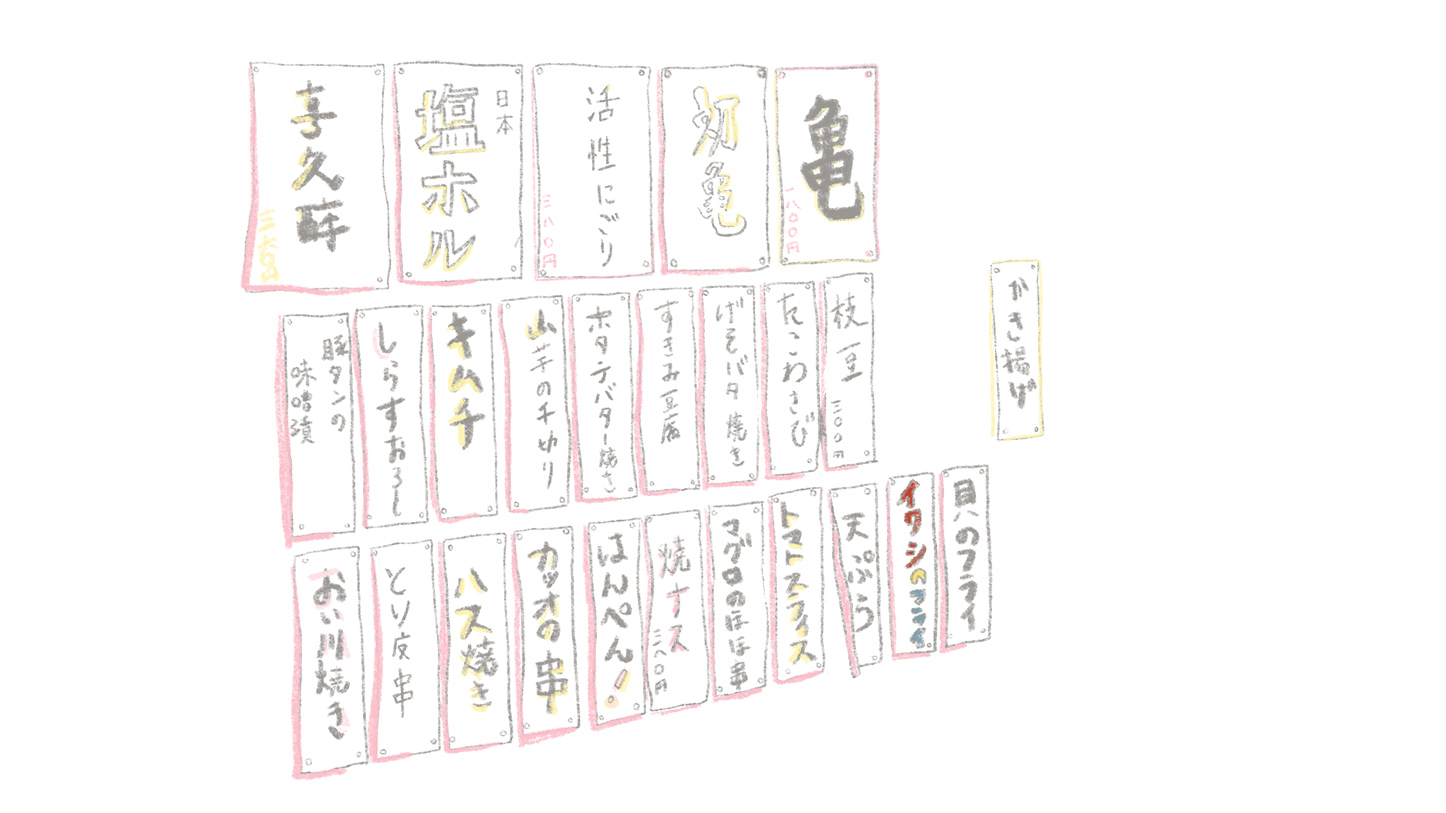

Yatai often had simple signs denoting what was on offer. Sushi, tempura, eel, and soba were popular, and a stall sign or paper lantern might simply say sushi, soba, or, more cryptically, 二八 (“2-8”) in kanji, which stood for soba, since the optimum ratio of wheat flour to soba flour is 20-80. Eschewing written menus, vendors laid food out for the customer to see and choose, a function of the stalls' limited space. Peddlers would shout out their offerings to attract custom. Illustrations from the era show that, in addition to signboards outside, indoor restaurants had food options written on strips of paper or wooden boards – akin to those we see today.

Mod cons

In the early 1900s, the proliferation of department stores gave rise to a new kind of restaurant culture. Originally aimed at the upper classes, department store restaurants became popular with Japan’s middle class after the 1923 earthquake that flattened Tokyo, according to food scholar and Nagoya University associate professor Nathan Hopson. The popularity of these restaurants was so great that stores had to introduce new methods of service to increase efficiency and turnover.

After the quake, the cafeteria at Tokyo department store Shirokiya – one of the pioneers of Japanese department stores – struggled to serve all its eager customers due to its significantly reduced floor space. Echoing the yatai street stalls of an earlier era, the cafeteria decided to let the food do the talking. “The store placed samples in a show window in the stairway so that customers could choose their order before reaching the cafeteria,” wrote Hopson in a history of Japan’s famous fake food. This innovation lessened the time the customer spent at the table. Initially, these models were created from wax, but during the war, paraffin became scarce, and polymer resin was used instead.

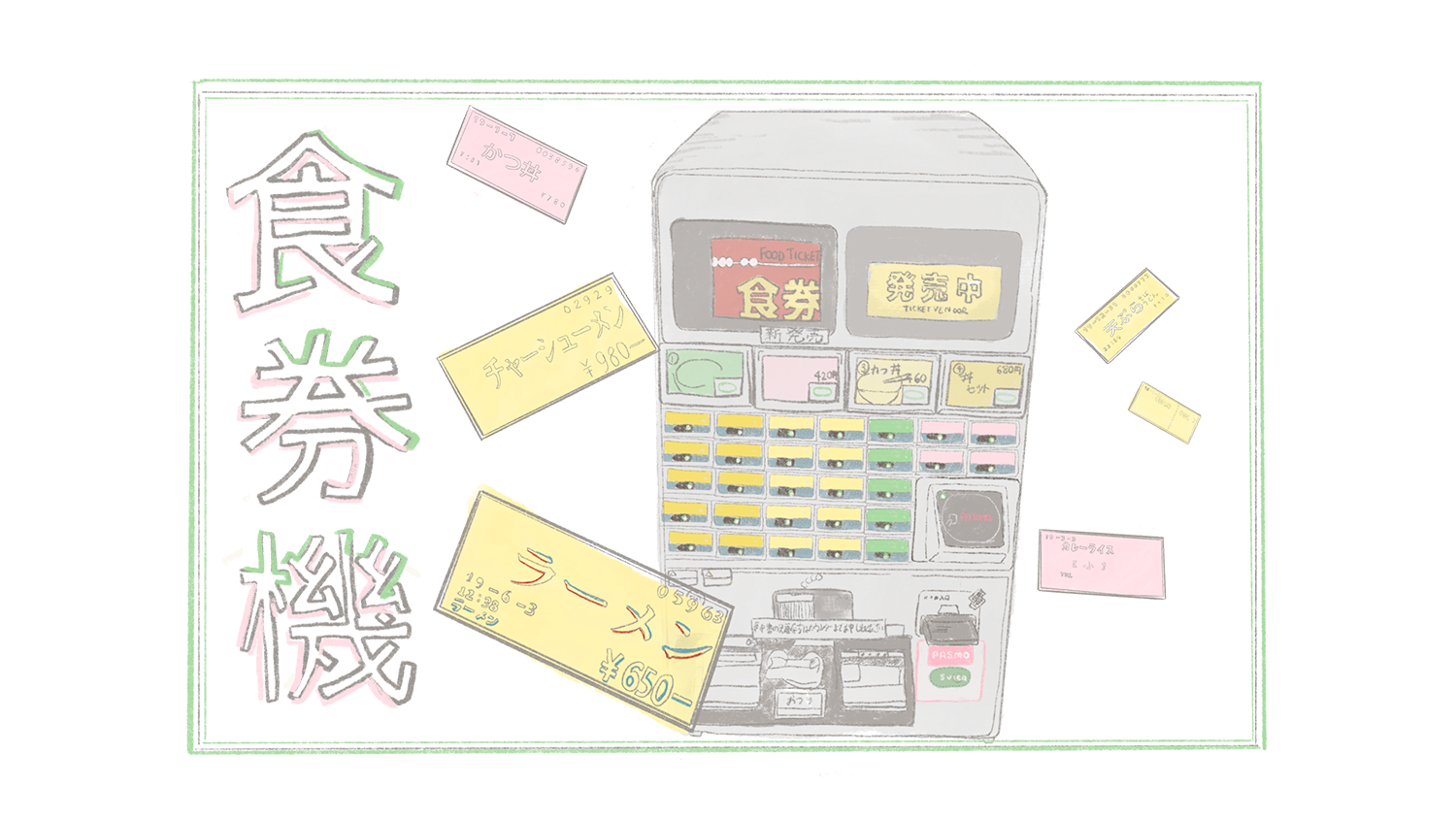

The second big change was the ticket machine, which took care of payment and ordering all at once, reducing interaction with servers. According to Hopson, train ticket machines were introduced at Ueno Station in 1926, and were adapted for use by the restaurant industry; proving to be exceedingly efficient, ticket machines soon spread beyond Tokyo restaurants.

By the 1930s, Japan’s largest department store cafeteria – inside the Hankyu department store in Osaka – began using ticket machines and samples. This innovation was a response to the demand of Japan’s growing middle class. According to Hopson, “the cafeteria at Hankyu was roughly four thousand square meters large and operated from 11am to 10pm. In July of 1936, the restaurant served a staggering 45,000 people per day, an average of over four thousand per hour...The use of samples and ticket machines allowed this extraordinary turnover rate.”

In July of 1936, the restaurant served a staggering 45,000 people per day, an average of over four thousand per hour... The use of samples and ticket machines allowed

this extraordinary turnover rate.

Menus today

Though the number of restaurants in Japan today is astronomical, reaching 150,000 in Tokyo alone, customs inherited from Japan’s first restaurants linger.

Rankings persist in some restaurants, especially in ryotei, restaurants which serve kaiseki multi-course menus. These are often encoded as matsu, take, and ume, 松, 竹, 梅 (“pine,” “bamboo,” and “plum”), three symbols of winter that are used to denote high, middle, and low ranks respectively. You may also see the less opaque tokujo, jo, and nami 特上, 上, 並 (“deluxe,” “upper,” and “regular”), or even A, B, and C sets. In each case, the top selection will be the most expensive, feature the rarest ingredients, and will also often have more dishes. For example, a C set might be a main dish and drink, while an A set would also include a salad, side, and a dessert.

Yatai stalls, though dwindling, still tend to serve a single dish or closely related series of dishes, and vendors still holler to advertise their fare. Many restaurants have a high degree of specialization, with Edo’s famous four foods: tempura, soba, eel, and sushi, still going strong. In many modern sushi restaurants, the day’s ingredients are laid out in a glass case in front of the chef, on display just like in the days of the yatai, so customers can see for themselves what’s on offer.

The practice of handwriting the menu on folded strips of paper in beautiful calligraphy is still common in kaiseki cuisine. In some izakaya and more traditional restaurants, menus still consist of kanji written on hanging strips of paper displayed on the walls, while paper lanterns still act as signals that an establishment is open to diners and drinkers. And in mid-range and budget restaurants all over, you’ll still find plastic food models and ticket machines at the door, symbolizing food that’s fast, hot, and no-nonsense.

Of course, you’ll still find the usual laminated menus with blocks of text. But whether you’re going for something cheap with pocket change and ticket machines, or fancier with finely lettered lines on delicate washi paper, Japan’s menus offer fascinating clues to the country’s culinary history and culture.

Though the number of restaurants in Japan today is astronomical, reaching 150,000 in Tokyo alone, customs inherited from Japan’s first restaurants linger.