A journey through the test kitchen at INUA

Text by Jessica Thompson

Photography by Sherry Zheng

Translation by JM Iitomi

Arriving at Inua mid-morning, the elevator that lifts guests from the restaurant's entrance to the dining room is dense with the smell of smoke. Not the sharp-smelling smoke that makes you want to reach for the emergency button, but the soft, reassuring type that smells of forests and mushrooms.

“We keep the smoker going 24/7,” says Thomas Frebel, Inua’s German-born head chef, as we approach the vertical smoker inside the service kitchen. The top shelf is lined with coral-like formations of maitake mushrooms; they’re a deep, dark shade of brown from five days of aging, compressing in rice koji oil, then three days of smoking. Thomas tells us that they’re then braised in a dashi stock of spruce pine needles from Hokkaido, and served topped with dried sakura petals.

“Our approach to creating is to celebrate and highlight things we believe are unique to Japan, existing only here – or at least, in a different way. It’s not about the fatty piece of tuna or the A5 wagyu meat.”

In 2015, Copenhagen’s Noma restaurant came to Tokyo for a five-week residency at the Mandarin Oriental, at which time Thomas was a 10-year Noma veteran. Hypnotized by Japanese ingredients and food culture, Thomas set his sights on a permanent project in Tokyo, opening Inua in 2018. The restaurant’s name comes from the Inuit mythology of Greenland, where an Inua is a spirit that connects all living beings with nature.

“Our biggest inspiration and biggest guidance is nature, staying connected to our surroundings, to the local ingredients, to the local traditions, to the local people. We celebrate those ingredients, those seasons, traditions, and techniques through the eyes of a stranger,” says Thomas.

Inua’s research and procurement teams connect with a network of around 150 farmers and producers across Japan. Their job, Thomas says, is to not just source ingredients, but to see what is happening around the ingredients, “to understand the culture and the country better, in order to distill these experiences onto the plate.”

As we walk through the weave of kitchens, stairwells, smokers, and refrigerators, to end up at the test kitchen, Thomas shows some of the ingredients he’s most excited about.

“Ingredients are like letters of a country and a landscape, which in the end, create an alphabet,” he says. “Many different ingredients create an alphabet, and an alphabet creates a language. So in the end, as humans, we are here to help a landscape speak.

Okinawa

“Okinawa is the perfect example of a tropical climate.”

“Okinawa is the perfect example of a tropical climate,” says Thomas. “It’s so different from the rest of Japan – it could almost be somewhere else in the world because of its climate.”

Canistel, or egg fruit, is a tropical fruit native to South America and cultivated in parts of Asia, including Okinawa. They have an unusual custard-like flesh, like the lovechild of a pumpkin and an avocado. “We discovered these two years ago, but we couldn’t figure out what to do with them. Now, I think we’ve found our way.”

At Inua, canistel are fried in tempura batter, and served with a paste of shiku (Japanese bergamot), rhubarb oil, roasted yeast, and kelp.

“We’re also trying to make miso with it, as it has a high-protein content and is low in fat, which is very good for miso,” says Thomas.

Pumpkin-bushi

“This one smells very Mexican, like dried chilies.”

Katsuobushi – dried, smoked and fermented bonito fish – is a cornerstone of Japanese cuisine; it’s the base for most dashi, an ingredient ubiquitous in Japanese dishes. Thomas presents what looks like a charred piece of bark, very different to the unblemished smoothness of preserved fish fillets. The gnarly form is not katsuobushi, but “pumpkin-bushi.”

“This one smells very Mexican, like dried chilies,” Thomas says. It’s sweet, acidic, smokey and could easily pass as ancho chili to the nose.

To get it to this point, a family of katsuobushi savants in Kagoshima treat the pumpkin the same way they would a fillet of bonito – a combination of drying, smoking and fermenting. Although Japanese in principle, making bushi from vegetables is not a traditional Japanese practice.

“The way we approach creativity is coming to Japan as an outsider. We have no preconceptions; we celebrate and highlight the things that we believe are unique to Japan, and which excited us the most.”

The pumpkin-bushi is shaved like katsuobushi, and the sawdust-like shavings taste like caramel. They’re used for a paste served with pumpkin that’s cured in kelp then steamed and barbecued; it’s served with rosehip berries, beechnuts and a sauce of barley koji.

Nagano

“This is an incredible spice, like sansho on LSD.”

Bunches of kihada berries hang drying on their branches from the lofty banisters of Inua’s test kitchen, others are in stacked containers with other native ingredients.

“This is an incredible spice, like sansho on LSD.”

Kihada berries are used to cure deer fat, and appear in a miso with locally-grown habanero chillies and yuzu peel.

Thomas then brings over a plate of what looks like frozen green olives; they’re sarunashi, wild kiwi fruit. Literally meaning “monkey pear”, the name is thought to come from the fruit’s popularity with the primates Nagano is famous for. Their flavor is bright and tangy, and when frozen, sarunashi are just like a sorbet. At Inua, frozen sarunashi are served as a palate refresher.

“When I think about kihada berries and the sarunashi, I think about Nagano, about the forests, the mountains, about the purity and clarity that prefecture can give me when I go there to disconnect myself from the concrete jungle of Tokyo,” says Thomas.

“In the same way, these two flavours remind me of that – something extremely original, beautiful, undiscovered… the hidden treasures of culture, people and stories that Nagano has to offer.”

Sansai

“I feel what comes from the cold, mountainous areas of Japan like Akita and Nagano, sansai and things like that, it really shows the essence of Japan.”

A type of daylily, yabu-kanzou sprouts with the other sansai (wild mountain greens) that herald the arrival of spring in Japan. From March until May, it grows wild on the ridges of mountains, along riverbanks and around rice fields – of which Akita, in the far north of Honshu, has plenty.

“It’s like a leek but not a leek, it’s better almost,” says Thomas, as he turns the vegetable – a stubby, pale green stalk topped with a bundle of dark leaves – on a countertop hibachi grill; the underside of it now slightly charred and giving off a sweet, onion-like smell. Once cooked, he brushes it with butter infused with pumpkin seed and green soybean tempeh.

Seaweed

“One of the main focuses we had before we opened was the seaweeds of Japan.”

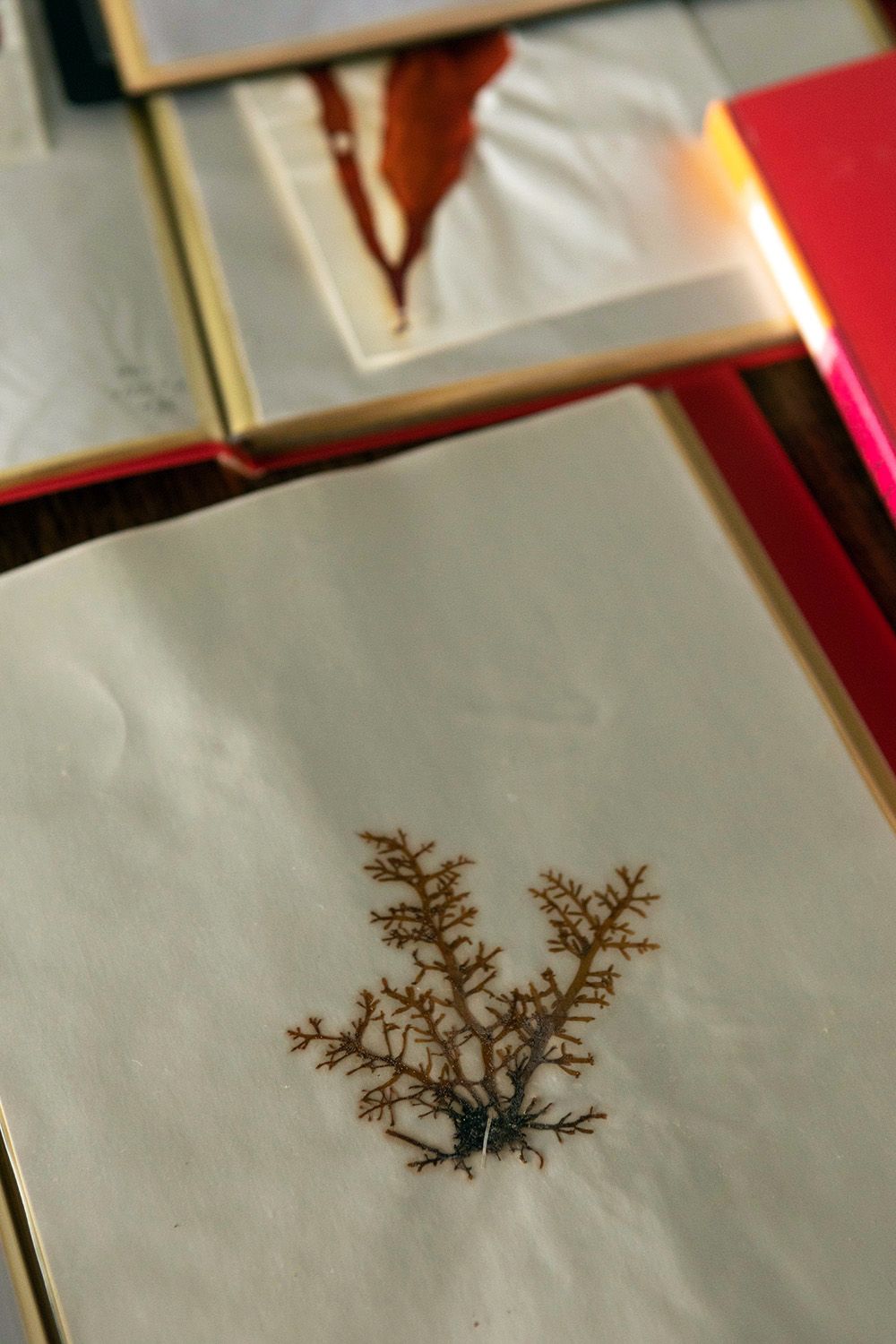

A large photograph of seaweed hangs in Inua’s test kitchen, indicating the almost divine status of seaweed in the restaurant’s dishes. “One of the main focuses we had before we opened was the seaweeds of Japan. We learned a lot, and what we learned the most is that we don’t know anything,” says Thomas.

“Our research team introduced us to a marine biologist from Fukuoka who has been diving for seaweed in Japan for more than 40 years. He connected with a group of people to help us source different varieties of seaweed, and also gave us his entire archive of dried seaweeds, which he had been building up for decades.”

Thomas pulls out some large scrapbooks of seaweed, inside are pages of pressed algae of mesmeric patterns and colors, a sweeping catalogue of an underwater garden. “We need probably two days to go through all of them,” he says.

One of the fresh seaweeds in the restaurant is hirome, a variety with wide khaki fronds, which is harvested in Wakayama from January to March. “One of the most appealing characteristics of hirome for me is that it doesn’t have much flavor, and it really likes to take the flavor of whatever you cook it in.”

Hirome is used for a dessert dish at Inua – it’s blanched in honey kombucha, dusted in powdered sugar and layered into a mille-feuille. Thomas says exploring seaweed has taught him there's "as much seasonality underwater as there is on land.”