Cultivating the past into the future

Photos by Joshua Cohen

In 2015, designer Teruo Kurosaki went to Takigahara, a village in rural Ishikawa prefecture, to investigate moss and found a town with “a rich spirit but dwindling numbers and a population with an average age of 70.” He also found a 140-year-old abandoned farmhouse.

“This was the only area in Japan where farmers used to rule society – in other places, samurai ruled,” says Kurosaki.

Inspired to revitalize the area, Kurosaki is creating an oasis of alternative ways of thinking and living.

“It is my hope the other cities and people will hear this and come here to learn. Then It becomes a kind of movement, a new type of village for the future.”

Today, Takigahara Farm has grown into a complex including a cafe, vegetable patches, rental accommodation and a natural wine bar. There are plans for artist studios, a gallery, a library, and more. The collection of spaces echoes the community focus on cultivation and nature.

The farm has three long-term residents, Ryo Ogawa, Miuru Yukinaka, and Naiki Yoichi, all aged between 20 and 40, who moved to Takigahara from Tokyo and its surrounds. Together they cultivate the fields, welcome guests, run the cafe, plan festivals, and help shape the future of the region.

This series of photos is from the spring of 2017, depicting key elements of the daily rituals and environment at Takigahara Farm. As Ryo, Miuru and Naiki reflect on the images, their recollections show how thoughts and conversations, whether shared or personal, are inseparable from a landscape and even help to define it.

This table is the core of our community.

Ryo: This table is the core of our community. Here, we share food and drinks with our local community, share ideas with people who visit us, and share staff meals.

One day, we sat around this table talking with our neighbors. They told us how, in the past, when people from the city came to rural areas, the city folk called the rural people poor because they couldn’t write, and their food was simple. But before these words were spoken, the idea of “poor” wasn’t known in the community, because people were able to sustain themselves – growing food, sewing clothes, managing their own water supplies. Now, we all have to learn the philosophy of these rural people, their understanding of nature. They learned how to be flexible and survive in tough times and to look after the land they are tied to.

...a bamboo forest spreads out in front of you, you can see a grandma tending to a field, and Mt. Kurakake in the distance.

Miuru: Right in front of you, a bamboo forest spreads out, you can see a grandma tending to a field, and Mt. Kurakake in the distance. I decided to stay because I was moved by this scenery – as well as the kindness of the people in Takigahara, and the richness I felt in my heart.

I still remember clearly when I first came to Takigahara in the summer of 2016. At that time, I was wondering whether living in the mountains, standing on the soil, could be a comfortable life for me. The locals often asked me why I would move to a place where there is nothing, but I felt this was a place where I could do anything.

I was trying to grow blueberries for the first time.

Ryo: I was trying to grow blueberries for the first time. After planting, I asked a good friend – an old local guy who farms blueberries for a hobby – he said, “it will take three years, at least.” I was shocked. I realized that I hadn’t ever thought about my life in three years’ time. I wasn’t even sure how long I wanted to live at Takigahara. It was then that I made up my mind to stay in Takigahara for at least three more years and take care of my baby blueberry bushes. Seeing this photo, reminds me that the future is more than I can imagine.

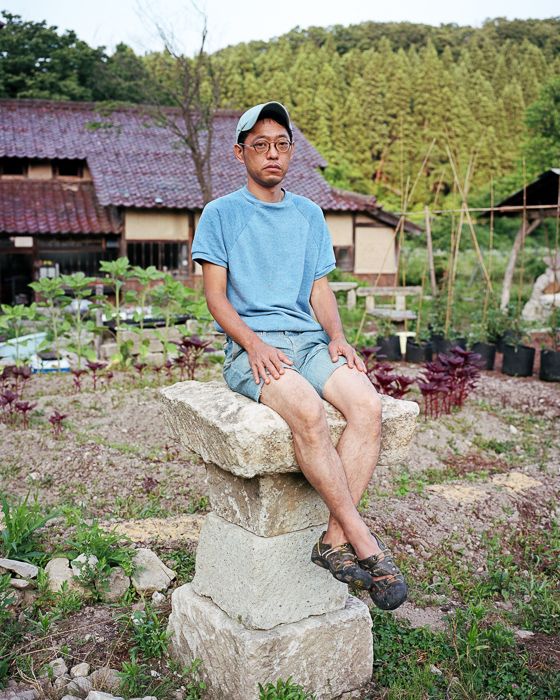

The stone I'm sitting on is Takigahara stone, the natural resource that represents this area.

Naiki: The stone I'm sitting on is Takigahara stone, the natural resource that represents the area. This stone is produced from a quarry near the Takigahara Farm, and because of its water-resistant nature, it’s used in many of the onsens in the area. Takigahara house, where we live, is a beautiful warehouse made out of Takigahara stone.

This stone oven, made from abandoned Takigahara stone, has given us so many memories.

Naiki: This stone oven, made from abandoned Takigahara stone, has given us so many memories. The first time we fired it was for the first Takigahara Festival. I asked a friend, Junpei Katsumi of Paradise Alley bakery in Kamakura (my home town), to make pizza and bread… [He] believes in leaving the bread-making to the yeast. However, that first time, the dough didn't rise until the very end of our Takigahara Festival, and the locals who had gathered so expectantly for the pizza and bread were disappointed. Now when I think back, it’s a good memory. It was difficult to learn to use a stone oven, but now, we can make delicious Naples-style pizza.

I joined the Takigahara Rice Farming Union recently.

Ryo: I joined the Takigahara Rice Farming Union recently. There are about 15 old guys in the union, most of them over 70 years old. I was surprised at the amount of land they tend to – it’s tough work for people that age. Each year, we make about 1,700 bales of rice (107,000kg) of three different kinds – Yumemizuho, Koshihikari, and Hyakumangoku. I’m always excited to see the brown land turn green in summer after planting and then golden in autumn, at harvest time. In the background you can see the stone quarry.

Early each summer, we harvest the ume… and make ume syrup.

Miuru: Early each summer, we harvest the ume (Japanese plums) in the area and make ume syrup. A few weeks after that, it’s time to prepare shiso syrup. It's very difficult to remove the plums and shiso from their branches one by one, but someone always comes to help. While we work together, there is always conversation; when we finish, we taste the syrup that we've made all together. Each year I wonder, “who will be making the syrup together this year? What kind of taste will the syrup have?”

...life itself is made up of seasonal rhythms.

Naiki: What I realize most about life in Takigahara is that life itself is made up of seasonal rhythms. Spring, when this picture was taken, is the season for wild plants. Everything that comes into view gives a lively energy to the fresh green sprouts in spring, and now it's easy to identify the edible wild plants from the view. Some kind of wild vegetables are always on the table during that season.

The Chinese root for the word "season" (shun) is actually associated with a time span of 10 days. Once I found this out, I was sad about how fleeting seasons seemed, but then also excited about encountering new beginnings and ends.